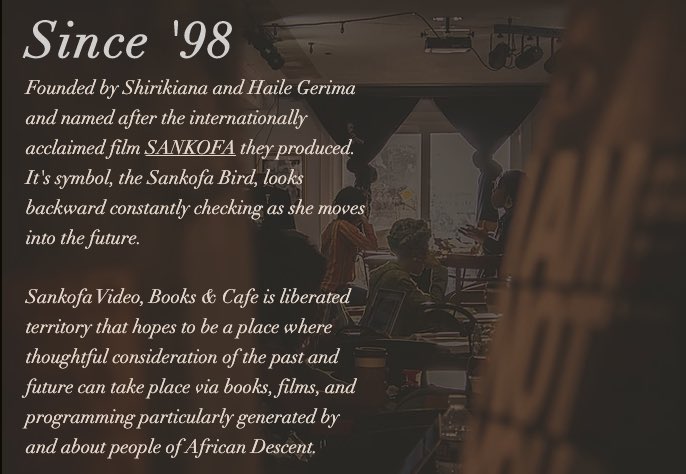

Sankofa is an event used by Saint Louis University to honor African-American student graduates and students who graduate with degrees in African American studies. The symbol and name were used in the 1993 film Sankofa by Haile Gerima, as well as in the graphic title of the film 500 Years Later by Owen 'Alik Shahadah. Sankofa is a Black filmmaker-family-owned and operated bookstore and cafe specializing in books, movies and programming about people of African descent since '98.

- Tye JMU class clip of Sankofa.

- While Mona (Ogunlano), a black American fashion model, cavorts for a (white) photographer during a shoot at a fortress town on.

Oyafunmike Ogunlano and Alexandra Duah - 'Sankofa' (May 1993)

Sankofa is an Akan word meaning roughly, “We must go back and reclaim our past in order to move forward.” Haile Gerima’s cinematic rendering of this is perhaps one of his greatest filmmaking achievements. Screened as part of the UCLA L.A. Rebellion Film Series, 'Sankofa' follows Shola, a black model who is transported back to a West Indian plantation after participating in a fashion shoot on shores of the slave castles in Ghana. Shola becomes a house slave alongside Shango, a militant Maroon fieldhand and love interest who resists her early warnings to ignore the brutalities committed against others on the plantation. Sexually abused by the plantation’s owner, Shola is drawn to Nunu, an African-born fieldhand and Maroon leader, who ignites her eventual rebellion.

As a student in Howard University’s MFA Film Program, I took a class with Haile Gerima, called Third World Cinema. In it, he challenged many of our notions and beliefs about filmmaking, especially when it came to telling stories about people of color. One of those challenges was to scrutinize black “stock” characters in American films, or those black characters that had no back-story, but were just there to uphold white characters’ place or status. He presented a number of films where this type of black character existed- 'Casablanca,' 'Gone With the Wind,' and even Douglas Sirk’s 'Imitation of Life.' All are classic Hollywood films, but they position the black body as one of complete servitude. There exists no richness or complication within these characters.

Gerima encouraged us to break and subvert that paradigm. To create black characters that were rich with inner turmoil, who resisted, struggled, who sought intimate relationships, and who possessed sensuality. It is on this foundation that 'Sankofa' rests. One of the film’s most revolutionary contributions is Gerima’s portrayal of enslaved people, not slaves. They are people struggling with love, loss, denial, and guilt. He takes them out of the one-dimensional, passive, “victim” role, and embodies them with complications that manifest in active resistance, personal conflict, and compelling stories.

In one scene, headman Noble Ali, played by Afemo Omilami, expresses his love for Nunu and she lightly rejects him, saying, “Don’t wait for me. I can’t be with no headman.” There is humor here, but there’s also pain as he shows deep remorse for aiding in the abuse of fellow enslaved people. This scene unpacks a character who could be easily labeled a “villain” in another film. But in this scene, we experience the inner conflict of a person who is forced to exact violence on his own people, while harboring a certain internal violence and pain for those actions. That violence inhibits his ability to form a loving relationship with another person. This is as heart-wrenching as it is grounded in the history that Gerima spent over 20 years researching.

Another important element of the film lies in its aesthetic and visual associations. There’s a continual presence and framing of the land and the character’s relationship to it. Close shots of Shango’s eyes through the green sugarcane stalk evoke a oneness of the black body to land, and of the land. A coexistence of power and ultimate universality is furthered. A low-angle shot of Shola standing amidst the cane stalks with a machete in hand exalts her to that of authority in this environment, and invites the viewer to see her as such. In one of his more daring but resonant sequences, he juxtaposes and equates images of Virgin Mary and Christian saints to Nunu, an African woman of profound wisdom whose son, the product of rape, becomes submerged in waves of self-hatred and religious fervor encouraged by the presence of the church.

When it was released in May 1993, Gerima embarked on an unprecedented distribution and promotional model that helped make it one of the most financially successful black films to date. Propelled by grassroots organizing, community support, and packed theaters, Gerima championed an alternative, highly successful route to independent film distribution outside of the studio system. And in light of recent films like Quentin Tarantino’s 'Django Unchained' and Steve McQueen’s 'Twelve Years a Slave,' I hope we look back to 'Sankofa' for its audacity to humanize and re-envision a people in a layered, complicated narrative form.

Nijla Mu’min is a writer and filmmaker from the East Bay Area. She is currently in post-production on her feature film debut, “Jinn.” Visit her website here.

Haile Gerima

By: Maya Lee and Davis Waln

Overview

Sankofa is a film that twists the typical perspective of slavery by challenging African-American and societal views. Written and directed by Haile Gerima, the movie was released in 1993 and starred multiple prominent black actors and actresses. Gerima used slavery to change the perspective of the past within the African-American community.

Opening scene of Sankofa with Sankofa guarding the castle.

(Sankofa. Dir. Haile Gerima. 1993. DVD.)

Sankofa’s opening scene is a black model, Mona, on a beach outside of an African castle. During this scene, Mona meets the guardian of the castle and assumes that he is a lunatic. After a few minutes of uncomfortable yelling between each other, Mona is transported back into the past and takes on the body of a slave. She lives her life among other slaves at an undisclosed plantation in America. Gerima mentions in an interview that not giving the movie a location was vital in its success. Without a setting, it becomes harder for viewers to brush the movie off because it generalizes where their ancestors were enslaved. Through these experiences, she witnesses the horrors of slavery and the associated racism.

At the end of the film, Mona is transported back to present day but still remembers her experiences from the plantation. Her memories from the past continue to haunt her, and she begins to see the everlasting effects of slavery in modern society. She realizes that Sankofa, the guardian of the castle, is not crazy, but is attempting to make slave descendants see the importance in connecting with their ancestors. By using a form of time travel, Gerima conveys the full extent that slavery continues to have on society and wants African-Americans to better connect with their roots.

Historical and Cultural Context

Sankofa bird, with feet planted forward, looking into the past to go better into the future.

(Berea College; Carter G. Woodson Center; https://www.berea.edu/cgwc/the-power-of-sankofa/.)

The word Sankofa is from the Akan culture of Ghana, and it embodies the idea of going back to the past to learn and better continue to the future. The character in the movie, that is named Sankofa, embodies this philosophy. This ideology, among many others, is emerging and perpetuating in modern society. Although not all that use this word understand its full meaning and origin, it is still very prevalent in society today, in literature, and even company names (Temple). The movie Sankofa is a bridge between the origin of the ideology and the meaning it holds in society today.

With the problems of modern society, the idea of Sankofa is more important than ever. The writer and director Gerima experienced racial violence and separation growing up in Chicago. There were race riots protesting ghetto conditions and police brutality throughout the time he was growing up there (Essig). Although a little more calm today, some of these problems that Gerima grew up with still are present in society. A specific case of police brutality at the time the movie was released is the case of Rodney King. Police officers beat him, it was caught on tape, and the wrongdoers were acquitted (Sastry and Bates). The movie was created as a response to the growing separation between the displaced African people and their heritage and roots. It showed them a way to be grounded and deal with the corrupted society that stifles and waters down their culture.

In the movie, a reflection of modern brutality can be seen when white slave owners beat the slaves. This kind of exaggeration of modern issues force the readers to see them, and they cannot ignore the flaws still haunting this country.

The movie was a voice of criticism to society, and a reminder to the displaced to look back and remember their past, as it is an incredibly important part of dealing with their current oppression. They need to learn about the wrongs of the past to understand the wrongs of today. Hardships the people originally from Africa are experiencing today is a major motivation for making this movie.

Haile Gerima’s upbringing in Ethiopia trained him to tell stories. He grew up from when he was born to the age of 10, listening to his grandmother tell stories that were passed down by mouth through the generations. He then moved to Chicago where he experienced first hand the culture surrounding race relations and racial violence (A Moment With… Haile Gerima). This combination of upbringing created a passion for creation and endless ideas to portray. Because of this fire, he fundraised the necessary money to make the movie, recorded it, and produced it in his basement. Due to its almost vulgar nature and risque topics, the movie had to stand independently, however it still attracted many curious eyes and sparked conversation in society today.

Themes and Style

The film Sankofa uses vivid imagery and displays of violence to drive the horrific scenes of slavery into the viewers’ minds. The scenes, although maybe disjointed and hard to follow at times, portray the best and worst parts of a slave’s life – from the comradery of family, to the murder of innocent mothers. The situations the director and writer chooses to depict appeal to the viewers’ ethos and pathos, making them feel the friction between morals and actions, and drawing out their most empathetic sides with emotional displays of loss and dichotomy.

The film’s overarching and reoccurring theme is the idea of Sankofa – don’t forget your roots. This is clearly seen in the literal transportation of the modern day model, Mona, into the antebellum past, and her enslavement. She learned about where she came from – from the hardworking and abused slaves. She remembers, learns, and knows that in her modern day life she must stay closer to her people and culture.

However, there are other themes that emerge throughout the movie. As Noah Berlatsky said in his article “What Movies About Slavery Teach Us About Race Relations Today”, “it is remarkably focused, even obsessed, with betrayal and faithfulness” (Bertlatsky). The unintentional betrayal of the displaced African people from their heritage is displayed in the character Joe, the overseer that turned on his own people and even his own mother. This theme of betrayal is a warning to the displaced, and creates antithesis to bring out the faithfulness themes in the film even more. Take the faithfulness of Shango, for example. His endless fire for rebellion and steadfast loyalty to his people against Joe’s betrayal creates a friction that cannot be ignored, and the movie makes it clear which path the writer thinks is right. Shango’s rebellious nature can be related to the rebellions of today, and black rights marches across the country. Shango remembers his past in Africa and being taken from there, and moves forward in his future accordingly. Through these examples, the movie clearly shows what is happening in the displaced people’s society, and what should happen instead.

The film explicitly shows the past, and its horrors. It shows how slaves were treated by their owners, and how they had to cope with their feelings of sadness and rage. They were beaten, raped, stripped of all rights and treated like things to be manipulated. It is showing the past and reminding the viewers that this did happen, and when watching, the viewers can’t help but pay attention and understand one of the ugliest faces of American history. The movie’s portrayal of such mistreatment is motivation for the viewer to not repeat a parallel of this mistreatment in today’s society, and essentially a reminder to all.

The film was created because of the struggles of the African American individual in modern society. Released in 1993 (however started much earlier), the film is a response to the segregation and hardships African Americans face. Unfortunately, some of the same hardships still exist in the modern day, and in her Tedx talk, Derise Atta described when she was little and told that girls don’t ride horses, and that black girls can’t wear bright colors like red. She then said how she used the idea of Sankofa to overcome even these small doubts. These kinds of negativities wear a person down, and Sankofa and Derise Atta’s lecture call for a change using the Sankofa ideology. In order to deal with microaggressions everyday, or even big aggressions, one must find an inner peace and be happy themselves so as not to be worn down to the bone. Go back to the past and to yourself, gain strength, and go forward in the future even stronger.

Critical Conversation

Haile Gerima reflecting on past projects and inspirations that continue to inspire change in the United States. (Haile Gerima. Digital image. Haile Gerima. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Apr. 2018.)

Although Sankofa was written almost twenty-five years ago, the perspective Gerima portrays is still relevant in modern society. In the African-American community, many remnants of slavery can still be seen today. From social inequality to racism, Gerima shows that maybe the western world is still not the best option for African-Americans. His movie argues that African-Americans should return to their roots in order to connect with ancestors. Derise Atta agrees with this view in her Ted Talk called “SANKOFA: Going Back to Fetch your Inner Voice.” She is a professor at Depaul University where she lectures on the importance of finding one’s roots. Gerima’s film and her lectures both agree and encourage people to join the Sankofa movement in order to find peace in society.

Many of Gerima’s personal experiences are exposed in his interview in the piece “For Filmmaker, Ethiopia’s Struggle Is His Own.” New York Times author Larry Rohter discusses with Gerima where his inspiration for the film came from. Gerima and Atta both share personal stories in their Ted Talk and Interviews, respectively. Gerima describes his first time coming to America as shocking. Coming from Ethiopia, he had never experience racism, but was appalled by what he witness in the land of the free. These occurrences drove him to write the movie Sankofa to force the African-American community to reflect on how they were being treated.

This movie was well received by its audience but challenges many trends in the Hollywood industry regarding slavery. Because of this, it was challenging for Gerima to gain funding for the film due to its controversial nature. Most films are only set in the past, causing many viewers to not fully connect with the characters, but Sankofa uses a modern perspective set in the past. Noah Berlatsky discusses this in his piece “What Movies About Slavery Teach Us About Slavery,” where he shows current practices in the film industry. By placing a current day model into slavery, Gerima shows how all of society is affected by slavery. Viewers better understand that slavery, despite ending over one hundred fifty years ago, still negatively affects them. This change in perspective creates an environment where viewers are immersed in the experience and better connect past events with current.

Haile Gerima Sankofa

To this day, the practice of Sankofa, returning to one’s roots, is still in use in America. Christel Temple writes for the Journal of Black studies and analyzes how the movement has gained popularity in recent years. She believes that much of the gain is due to films such as Sankofa. Many current social trends in America can be traced back to the idea of Sankofa and achieving a better quality of life. Gerima’s message continues to be heard to this day and inspires many social movements to better one’s life.

Works Cited

“A Moment With… Haile Gerima.” ResearchChannel. Feb. 2008. Interview.

Atta, Derise. “SANKOFA: Going back to fetch your inner voice.” TED. Jun. 2016. Lecture.

Berlatsky, Noah. “What Movies About Slavery Teach Us About Race Relations Today.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 2 Jan. 2014, http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2014/01/what-movies-about-slavery-teach-us-about-race-relations-today/282734/.

Essig, Steven. “Race Riots.” Chicago History, www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1032.html.

Rohter, Larry. “For Filmmaker, Ethiopia’s Struggle Is His Own.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 29 Mar. 2010, www.nytimes.com/2010/03/30/movies/30teza.html.

Sastry, Anjuli, and Karen Grigsby Bates. “When LA Erupted In Anger: A Look Back At The Rodney King Riots.” NPR, NPR, 26 Apr. 2017, www.npr.org/2017/04/26/524744989/when-la-erupted-in-anger-a-look-back-at-the-rodney-king-riots.

Temple, Christel N. “The Emergence of Sankofa Practice in the United States: A Modern History.” Journal of Black Studies, 1 Sept. 2010, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25704098?Search=yes&resultItemClick=true&searchText=sankofa &searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dsankofa&refreqid=search%3A0c4ca302d4c644da331d250836efb383&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Further Reading

Jordan, Coleman A. “Rhizomorphics of Race and Space: Ghana’s Slave Castles and the Roots of African Diaspora Identity.” Journal of Architectural Education (1984-), vol. 60, no. 4, 2007, pp. 48–59. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40480850.

Kande, Sylvie. “Look Homeward, Angel: Maroons and Mulattos in Haile Gerima’s Sankofa.” Research in African Literatures, vol. 29, no. 2, 1998, pp. 128-146, ProQuest Central; Research Library, http://prx.library.gatech.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/207655903?accountid=11107.

Turner, Diane D. and Muata Kamdibe. “Haile Gerima: In Search of an Africana Cinema.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 38, no. 6, July 2008, pp. 968-991. EBSCOhost, prx.library.gatech.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ahl&AN=32667718&site=ehost-live.

Sankofa Full Movie Youtube

Green, Percy, et al. “Generations of Struggle.” Transition, no. 119, 2016, pp. 9–16. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/transition.119.1.03.

Sankofa Film

Keywords

Sankofa Haile Gerima Full Movie

Sankofa, Roots, Betrayal, Loyalty, African Heritage